Canine Lyme disease, also called canine Lyme borreliosis, is among the most familiar tick transmitted infections known to occur in humans and dogs residing in North America. Despite being the subject of many studies, canine Lyme disease continues to generate considerable controversy in clinical practice, particularly as it pertains to exposure risk, diagnosis, consequences of infection, and even prevention. Controversy within the veterinary population always results in confusion with clients. Hopefully addressing the controversy and current recommendations will help if you are one of those that are confused as to what is the best thing to do for your dog.

Transmission: Hosts and reservoirs

Borrelia burgdorferi, a spirochete bacteria, lives on a variety of wild animal reservoirs. This ranges from rodents (particularly the white-footed mouse), to other small mammals (eg. chipmunks), and ground feeding birds (eg. American robin).

Vector:

The black-legged tick, or deer tick, that will attach to, and parasitize these mammalian hosts, as well as birds, unwittingly transfers the disease to other mammals, including dogs and humans.

Food source:

White-tailed deer, often associated with Lyme disease, are NOT reservoirs for B. burgdorferi. They are, instead, blood-feeding stations (and transport vehicles) for adult black-legged ticks. In recent years, increased deer tick populations are believed to be a result of similarly increased deer populations.

Prevalance & Distribution: Human prevalence

In August 2013, preliminary results from 3 related studies conducted through the CDC suggested that approximately 300,000 people in the U.S. are diagnosed with Lyme disease, each year. This is a significant increase from 2012 estimates of 30,000 reported cases. Of reported cases, 96% occurred in 13 states, particularly the northeastern U.S. and Upper Midwest.

Canine prevalence:

Canine Lyme disease is not reportable, thus precise estimates are unavailable. However, compared with humans, dogs in endemic regions are at substantially greater risk for exposure to infected ticks. Surveillance reports of dogs with positive antibody test results suggest that up to 85% of dogs living in endemic areas are at risk for infection.

Geographic distribution:

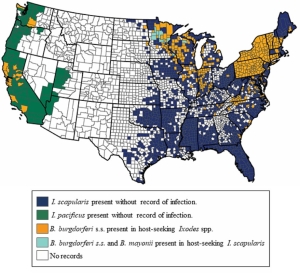

Today, risk extends beyond the traditional boundaries: the New England states, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, with a relatively high number of infected dogs reported annually in northern California, Oregon, and parts of Washington State. Anecdotal reports from practitioners in western Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and central Illinois state that the risk is spreading in their areas.

Surveillance studies in the U.S. and Canada, and Europe, indicate that both climate change and migratory ground-feeding birds contribute to movement of infected ticks, increasing the risk for both human and animal exposure. These studies highlight the need to increase surveillance, though routine testing of dogs living in those high risk regions.

Yet, this raises many important questions:

-What does a positive test result mean?

-Does an infected dog get long-lasting immunity to it?

– Should a dog with a positive test result, but without clinical signs be treated for Lyme disease?

-Should a dog with a positive test result be vaccinated for Lyme?

What do the experts say:

Diagnosis:

The confusion and controversy amongst veterinarians lies, in large part, to the fact that a clear definition of what constitutes a diagnosis does not exist. The recent introduction of laboratory-based and point-of-care testing technologies has muddied the waters still, when faced with a positive testing dog.

IMP: there is no single perfect test to diagnose Lyme disease.

Point of care tests: Snap tests (SNAP 4X AND SNAP 4DX)are often run while you wait in the office. Sometimes they are done at an outside lab. The good thing about these tests is that they are rapid, and are valuable as a screening tool for exposure risk. NONE OF THE COMMERCIAL LYME VACCINES CAUSE FALSE POSITIVE RESULTS on these tests. This important and a common misconception among clients. In other words, if they are vaccinated for Lyme, that does not mean that they will always test positive on the test, and therefore it does not mean that they should never be tested if they get the vaccine.

However, a positive test cannot be used to predict the clinical outcome of an infected dog.

Laboratory-based tests: Because the majority of dogs infected with B. burgdorferi have no clinical signs at the time of testing, use of the laboratory-based, quantitative C6 antibody assay has been used to diagnose, and often monitor treatment response. By quantitative, it gives you a numerical value. A number over a certain level is determined significant and repeat testing can be used to determine response to treatment.

Another diagnostic test (AccuPlex4) can defect 5 antibody responses to the presence of the spirochete. It also reportedly differentiates between natural exposure and vaccination as well as distinguishing early from chronic infection. However there are some limitations, which include the inability to identify acute infection in dogs vaccinated with certain vaccines. Also it is limited in the ability to reliably distinguish between dogs that test positive due to chronic infection compared to those that have been treated and then re-infected. And, it unable to consistently and reliably detect one tip of antibody produced with vaccination only. So it affects the interpretation and your vets confidence in the interpretation.

And remember, dogs can be re-infected. Another common misconception is that once they test positive on a test, they will always test positive. I have seen many dogs test positive, be treated, test negative for years, and then retest positive.

SO before diagnosing, the clinician must consider the physical exam finding and the lab findings. They must determine the exposure risk. Ideally, they should follow up a positive test with other bloodwork, and check for blood abnormalities not obvious on the exam. Also, these dogs are often co-infected with other pathogens. The combination can make signs worse. And you may not see the more expected signs of lameness, and yet serious disease may be present.

A severe version of Lyme disease that can show up on blood without obvious signs early on, is Lyme Nephropathy, or kidney disease. It is a rare, but often fatal, syndrome.Certain breeds seem to be more likely to develop this form of the disease, although any breed may be infected. Studies have shown that 30% of these dogs show signs of arthritis and approx. 30% have even been vaccinated.

Suggested Therapy:

– For dogs that test positive and do not have clinical signs, or lab tests that are unclear, most northeastern U.S. veterinarians tend to support treatment. C6 antibody tests are often recommended to further determine how much of an antibody response is occurring, and thus disease process may be ongoing, yet not obvious. Non-endemic area veterinarians may or may not treat in this manner with a non-clinical positive dog.

If treating a C6 tested dog, many doctors will recommend a follow up , or convalescent C6 antibody titer. This becomes important when you have a dog without clinical signs, and thus don’t have clinical improvement to use as a barometer of a response to antibiotics. They typically repeat the test 6 months later.

– For dogs that are clinical, antibiotic treatment is indicated and not discontinued until there is clinical cure.

Vaccination: Because vaccines are not 100% effective, and because there are risks associated with reactions to this and all vaccines, not everyone chooses to vaccinate. And, there is an ongoing controversy that there may be a risk of kidney injury with vaccination. Yet, that has not been proven, and it was, in fact, shown that 70% of dogs that had confirmed Lyme nephropathy, the severe form of Lyme disease, had NEVER been vaccinated for Lyme.

What is important is that the protection from natural exposure is short lived, and much shorter than the protection created with a vaccine. Many doctors recommend early and compliant vaccination, year-round tick control in endemic regions, and blood testing of dogs routinely to try to determine whether dogs are exposed and not obviously clinical, until it is too late to intervene medically.

So what does this all mean to you? The most important way to look at the disease is it is much better to prevent if than to treat, and possibly retreat. That is the single most important thing, in my opinion. There are many options to prevent tick exposure, and no one way is the best way. Lyme vaccines help prevent Lyme disease, but do not protect your dog, and you, from the other tick born diseases that are out there and are on the rise. And if your veterinarian tells you your dog tests positively, and makes a recommendation, really think about what is discussed. It is important to make sure that the decision you make is an informed one. I hope this information will come in helpful.

Dr. Dawn

Please share and subscribe here